[Note: This essay is adapted from a lecture delivered by the author at Utah State University in October, 2017; video of the lecture is available here.]

Raise your left hand in the air and keep it there.

Did you do it? If so, you are extraordinary. A strange woman just told you to do something, and you listened. On a historic scale, that’s not just different. That’s revolutionary.

There are a lot of people in the world who wish you hadn’t done it. People who don’t like me personally, because I’m the kind of woman who gets up in the front of the room and starts telling people what to do. People who don’t like me in theory, because of what I represent to them. People who you know. People who are participating in a cultural narrative that is woven into the fabric of our society.

I’m not mad at these people, even though some of them have threatened my life. Even though some of them have threatened my family. Even though some of them have said they’d like to come to my home and shoot me in the head rather than see me continue standing up at the front of rooms, telling people what to do. I’m not mad at them, and I’m not scared of them. Because I recognize what they really are.

They’re terrified.

Of course they’re terrified. For millennia, Western society has insisted that female voices—just that, our voices—are a threat. We’re afraid of wolves, and we’re afraid of bears, and we’re afraid of women.

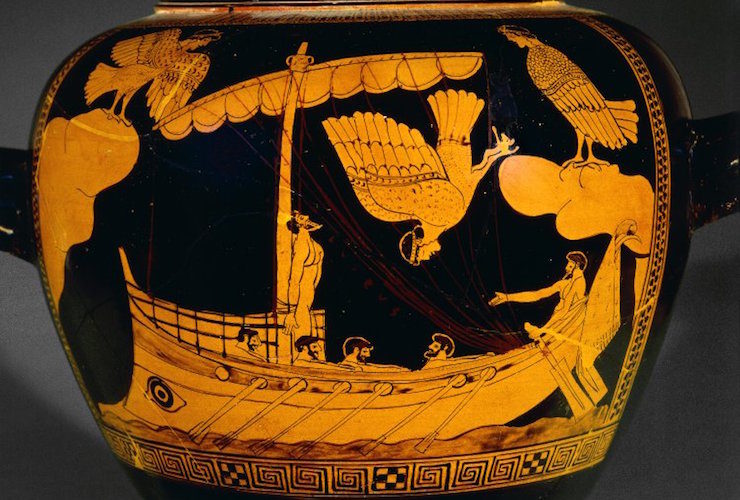

Pictured above is Odysseus, the titular hero of Homer’s Odyssey. In this picture, he’s resisting the call of the Sirens. The Sirens, for those who don’t know, were cursed women. In some versions of the myth, they failed to find Demeter’s daughter, Persephone, when she was kidnapped by Hades, the god of the underworld. As punishment, they were imprisoned on islands and trapped in horrible chimeric half-bird forms.

For the women who became Sirens, the curse was being marooned on islands, trapped for eternity. For the men who dared to sail too near, the real curse was the Sirens’ voices. Those voices were a curse because they could lure any sailor that heard them to the Siren’s islands, where the sailors would inevitably shipwreck and drown. Odysseus was set to sail past those islands, but he had a plan. He commanded his sailors to plug their ears with beeswax and cotton, and told them to lash him to the mast and not release him no matter what. He didn’t have any earplugs in for himself: he wanted to hear the singing and see if he could resist it. But when he heard the Siren song, Odysseus—a hero on a literally epic scale—was tempted. He was so tempted, in fact, that the only thing that kept him from commanding his sailors to change course and sail to their deaths was their inability to hear his commands.

This story is a great summary of the cultural fear of female voices. In a society where men hold power, the most powerful thing a woman can do is to have influence over men. The idea of a member of an oppressed class influencing the powerful is fundamentally threatening to the existing order of society, because it puts some degree of power into the hands of those oppressed people. So, when the Sirens sing and Odysseus can’t resist being drawn in by their song, the reader sees an epic hero displaying a rare weakness: these women are so potent and dangerous that they can bring down a figure as powerful as Odysseus.

This is just one example of a significant theme in Greek mythology. Sirens appear in several different stories from Greek myth, and those stories all reflect and reinforce our societal terror of the influence of women on powerful men.

Starting in the fourth century A.D., Siren mythos began to be subsumed by Christian writers and became a tool of allegory.

Saint Isidore of Seville, who was an archbishop for thirty years and who is often called the last father of the Christian church, wrote about Sirens. His etemologae, which was intended to be a collection of all human knowledge, supposes that the Siren mythos is actually an exaggerated accounting of Sicilian prostitutes. Saint Isidore wrote that those women presented such temptation to travelers that they would bankrupt them, causing their innocent victims to ‘drown’ in the pleasures of the flesh.

Christian art through the renaissance period uses Sirens as metaphor for temptation and ruin. These Sirens are often depicted as human-fish hybrids (hence our contemporary conflation of mermaids and Sirens). During the Renaissance, the Jesuit writer Cornelius a Lapide described all women as Siren-like temptations when he said: “with her voice she enchants, with her beauty she deprives of reason—voice and sight alike deal destruction and death.”

Initially, Siren mythos reflected an existing fear of the female potential to tempt and ruin powerful men. But over the course of centuries, their story grew into a tool to reinforce that fear. Sirens grow from a few sisters stranded on an island by a curse, to a working class of Sicilian prostitutes, to all women. When Lapide wrote that ‘voice and sight alike deal destruction and death’, he was speaking into a fear that stretches all the way back to Eden narratives—a fear that listening to a woman is a mortal error.

In 1837, a man by the name of Hans Christian Andersen attempted to defang the developing Siren narrative by writing a story called Den lille havfrue…

…which you may know better as “The Little Mermaid.” The original story, as our buddy Hans wrote it, is a Christian fairy tale about a virtuous Siren. His story is about an unnamed young mermaid who wants nothing in the world so much as a human soul, so that when she dies, that soul can live forever in the Kingdom of God.

She goes to a sea witch who gives her a potion that will grant her legs, allowing her to go up onto land and seduce herself a prince. The deal is simple: if she marries the prince, she’ll get a portion of his soul for herself, and she’ll be practically human. All she has to give up in exchange is her tongue and her voice. At the end of this original story, she doesn’t get her prince—he’s going to marry someone else, and she’s going to turn into seafoam. Her sisters—Sirens always have sisters—make their own enormous sacrifices to the sea witch in order to get the little mermaid a knife. She’s supposed to use that knife to kill the prince, which would let her turn back into a mermaid and rejoin her family. But because she is virtuous, she says ‘no thanks,’ and she dies, and she turns into seafoam.

Her reward for this enormous display of virtue? She’s trapped in purgatory for three hundred years, with the promise that at the end of that time, if she’s performed enough good deeds, she’ll get a soul and go to heaven.

Note that the overarching theme of this classic children’s tale isn’t love. Marriage is a factor, but it’s secondary—it’s a means to an end. What the little mermaid really wants—what she sacrifices everything to get—is a soul.

And the way for her to get that soul?

Silence.

She has to give up her voice, and she has to endure agonizing pain, and she has to reject the company of her sisters. All this just to get to purgatory, where she has to undergo additional purification in order to have a soul. Her existing identity as a woman who wants things and can speak to that want is a moral obstacle to be overcome; her only shot at redemption comes to her via silence and death.

This isn’t a new concept. Two hundred years before Hans Christian Andersen redeemed a Siren by cutting out her tongue, a guy named Thomas Wilson wrote the first English text about rhetoric. In it, he asks: “What becometh a woman best, and first of all? Silence. What seconde? Silence. What third? Silence. What fourth? Silence. Yea, if a man should ask me til dowmes day, I would stil crie, silence, silence, without the whiche no woman hath any good gift..”

But the explicit demand for female silence isn’t an old concept, either. Women in contemporary media face an overwhelming demand for our silence.

One can trace explicit objections to female voices through to the Golden Age of radio. During that era, radio personalities were overwhelmingly male, and the voices of women were considered unbroadcastable. Women who tried to break into radio were criticized as shrill and grating; their voices were high and breathy at the time because they were required by the society they lived in to wear corsets and, later, tight girdles. Those undergarments kept them from being able to speak from their diaphragms, and the result was a voice which we currently affiliate with a young Queen Elizabeth: slightly breathless, high and airy. Those women’s voices were criticised as lacking gravity. In reality, they were lacking in air, because the culture of the day demanded that they suffocate. Medical professionals insisted that corsetry was necessary for female health—which left women with a choice between silence and survival.

Today, women are more present in broadcasting—but they’re still subject to consistent criticism focusing on the way their voices sound, and not because they’re shrill. Instead, the primary focus of contemporary criticism of women in broadcasting is their use of something called glottal fry. Glottal fry, which is sometimes known as vocal fry, is a distortion of the voice which generally stems from an attempt to speak in a lower register without adequate breath support. Glottal fry has come to be closely affiliated with stereotypes of vapid, thoughtless women, when in reality, it’s a vocal tic that reflects a woman’s attempt to speak in a voice that is deeper, and thus more masculine, and thus—per the strictures of our society—inherently more authoritative.

It doesn’t matter if we’re speaking in our natural registers or trying to reach for the registers demanded of us: Women in roles which focus on speech simply can’t win. This was summarized most concisely by The Daily Express, which, in 1928, described female radio voices as universally unbearable by saying: “her high notes are sharp, and resemble the filing of steel, while her low notes often sound like groans.”

This same discomfort with female speech extends into online spaces, where an entire culture of harassment against women has become an embedded part of the experience of being a woman in a position of high visibility. These harassment campaigns are global and insidious. They target women who disobey Thomas Wilson’s edict about female silence, and include explicit threats of violence, rape, and murder.

They target women ranging from actresses like Leslie Jones, who starred in Ghostbusters and dared to go on a publicity tour, to politicians like Jo Cox, a British Labor Party MP who was shot and stabbed to death in response to her advocacy for Syrian refugees, to feminist media critics like Anita Sarkeesian. Notably, Sarkeesian had to cancel an October 2014 speaking engagement due to the volume of threats leveled against her and the University at which she was supposed to speak. These threats included the usual promises of rape, murder, and violence—but they extended into threats of mass murder and terrorism. One of these threats promised that “a Montreal Massacre style attack [would] be carried out against the attendees, as well as the students and staff at the nearby Women’s Center”.

The historic and contemporary demand for female silence stems directly from fear of what women’s voices can do. If women can speak to each other and to the world at large, the ideas of women threaten to influence and shape society from the top down in the same way that men’s voices have for centuries. This fear—the fear that women will influence men, and the fear that they will influence culture on social and political levels—is pervasive, and leads directly to violence.

So what’s the solution?

This. This right here. I’m doing something that for centuries women have been told not to do: I’m using my voice. And you? You’re doing something that for centuries has been considered anathema.

You’re listening.

Keep doing that. No matter who you are, no matter what you believe, regardless of your gender identity: listen. Keep listening. Listen even when it’s uncomfortable. Listen even when it makes you question the things you assume to be true about your life and the world you live in. Find ways to amplify the voices of women who are speaking. And if you’re a woman who has been afraid to speak?

You have two options. You can be silent. You can let that history of fear and violence shut you up. You can give in to those people who would prefer to see people like me in the ground. It won’t make them change the way they treat people who look and sound like you, and it won’t make you feel any less scared, but it’s an option.

Or. You can do what I’m doing right now. You can be everything that those scared people don’t want you to be. You can be outspoken, and opinionated, and confident. You can use your mind and your voice to change the way that people think, so that there’s less fear, and less hatred, and less violence, and less murder. You can be exactly as powerful as they fear, and you can use that power to make the world safer for other women who are afraid to speak.

You can be a Siren.

Your voice has power.

Use it.

Hugo and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey is an internationally-published writer of fiction and nonfiction. Her work has recently appeared in Mashable, the Boston Globe, and Fireside Fiction. She is a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to her work here. She tweets @gaileyfrey. Her debut novella, River of Teeth, and its sequel Taste of Marrow, are available from Tor.com.

Hugo and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey is an internationally-published writer of fiction and nonfiction. Her work has recently appeared in Mashable, the Boston Globe, and Fireside Fiction. She is a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to her work here. She tweets @gaileyfrey. Her debut novella, River of Teeth, and its sequel Taste of Marrow, are available from Tor.com.

Cockpit computer voices are female in tone because they get quicker attention than male voices and can be better heard over background noises. What is the first voice we all listen to and obey? Our mother’s.

keep on talking.

And writing. J. Austen: “Men have had the advantage in writing their own story. The pen has been in their hands.”

Literature as often been a means for women to make themselves heard.

Well said. Thank you.

A good message for all of us to ponder.

There are, of course, no shortage of accounts of lying men with their silver tongues, but yes, it does seem a lot of sexism exists, and remains entrenched.

I truly don’t understand this in the modern context. Didn’t we all grow up with female school teachers? In elementary school I had a male teacher in Grade 4, but otherwise, women. How do you not learn to respect women when you spend that much time being cared for and educated by them? Even though I was being raised with my Brother by my Father as Mom had escaped the situation (Dad wasn’t that bad, they just didn’t get along).

Nonetheless, is it little boys who do not respect their teachers that grow up to be dicks that don’t respect women generally?

There is a certain amount of cherry picking going on in the selection of examples. The Greeks were pretty misogynistic and frightened of strong women BUT Socrates credited a woman, Diotima, as his teacher in ‘erotics’ (not what you’re thinking). And Odysseus listens and obeys Athena his patron goddess because he knows what’s good for him. Helen of Troy not only turns heads but has loads of charisma and is clearly boss back in Sparta with Menelaus.

It does our ancestresses no service to portray them as shrinking, silenced, helpless creatures in the grip of a totalitarian patriarchy. Misogynistic attitudes certainly existed and were acceptable in a way they aren’t today but they were not the whole picture. Religious writers portrayal of women as Eve-like temptresses was counter-balanced by the veneration of Mary Queen of Heaven, Mother of God with a parent’s authority over Him. The courtly tradition of powerful women being served by loyal and devoted men also existed and could be used in real life to tame and control males as Elizabeth I proved.

This is an interesting read. It’s very well written and very well thought out. The original Little Mermaid absolutely supports your general theory with it’s odd Dark-Aged Christian tones. But a stronger argument could be made that the lure sirens call is’t a warning to men that women need to be silenced, but rather a reminder that women have power over men. In literature the most brutal of men even in the darkest male dominated setting can be swayed to eveness by the words and voice of woman.

The sirens call can certainly be interpreted as a condemnation of women and a warning. But isn’t it a better take away to say that even in barbarous times and settings – throughout history man’s tendency to dominate can be offset by love tenderness and empathy?

I’ve always seen it as a statement. That no matter what your course no matter what your destination no matter what your trajectory in life might be, if you meet the right woman, everything changes. She might dash you upon the stones or she may in time provide you with that with which lead you to your ascendancy.

Well said. Keep talking….and writing! Thank you!

There are some interesting historical insights here. One that I’m surprised the writer didn’t mention is the Orthodox Jewish prohibition on kol isha, or listening to a woman’s singing because a woman’s voice can be alluring to a man.

I don’t fully agree that women’s voices are categorically feared in Western society today. As a woman, there are times and contexts when my words seem less valued than a man’s. Luckily, they are not that common in my experience and people are quick to call out bad behavior.

@7 DougL

Good point, but I also think some children are still raised in homes or communities where older ideas prevail. Education is an important way to expose people to ideas about equality, but can’t always break through attitudes modeled by parents.

This reminds me a of a woman I know who kept telling women to use their voice and be heard. But then my mother said something contrary to that woman’s own beliefs and then that woman, that champion of women’s speech, was suddenly telling my mother to be quiet.

The meaning of this whole comment of mine is that, sometimes, it is not always men who are afraid of a woman’s voice. Sometimes it is women themselves who are afraid.

The question is, is it the sex of the speaker or what she’s saying? Because arguing with a woman’s ideas or opinions is not silencing her.

11, oh, the hostility of the world is not by any means limited to the chan-boards, or the Reddits, or Gabs, or even Twitterers.

13, or maybe your mother was not expressing herself appropriately. It happens.

@14 If telling someone they are not allowed to have a dissenting opinion isn’t silencing, what is?

17, telling someone they can’t tell somebody else to shut up is also an act of silencing.

Interesting examples. Desiring the ocean as badly as anyone ever desired sirens, I always thought of them as personifications of its agonizing allure. If I thought of them as beings, it was only to envy their aquaticness. But people who feel differently could indeed have created them as cursed and cautionary.

I can’t say that your reminders about the danger of speaking out, as a woman in the modern world, have made me more emboldened to do so.

A very powerful piece. Got me thinking. Though as a man married to a strong woman for 39 years, (sorry happily married to a strong woman for 39 years). I can see there is a difference in attitudes today. I enjoy seeing a misogynistic male trying to quieten my wife.

Fantastic article.

it just so happens that I’m reading Mary Beard’s book Women and Power right now. She also analyses historical examples of when women have been told to shut up.

she too chooses to use her voice, to challenge the trolls.

7 – “How do you not learn to respect women when you spend that much time being cared for and educated by them?”

Because it used to be a mark of male maturity to escape the authority of women: mothers, nursemaids and other servants, and teachers. (I hope that is changing.) First example I can think of is Telemachus telling his mother Penelope to stop talking in the Odyssey – Hector tells his wife to stop trying to keep him from going to fight Achilles in the Iliad, but that’s a different relationship, even though all the fears Andromache expresses are realized.

8 – “It does our ancestresses no service to portray them as shrinking, silenced, helpless creatures in the grip of a totalitarian patriarchy.”

Showing what they were up against does not show them as helpless. It does them the service of honoring their courage in persisting. For example, Hypatia, the philosopher, continued to teach and speak publicly in Alexandria until she was murdered by a Christian mob incited by a bishop who was later canonized.

19 – “I can’t say that your reminders about the danger of speaking out, as a woman in the modern world, have made me more emboldened to do so.”

I understand, but a knowledge of the dangers makes women better equipped to deal with them, highlights the courage those who persist and gives them another reason to keep doing so.

The Hypatia story is a lot more nuanced than the pop version.

Hypatia was recognized as an important philosopher and teacher and prominent and influential figure in Alexandria. She counted Christians as well as pagans among her students and admirers meaning that neither she nor philosophy were regarded as anti Christian.. Unfortunately for her she was also a good friend of the

Oops hit the reply key too soon.

Hypatia became involved in the quarrel between her friend Orestes the Prefect of Alexandria and Bishop Cyril and so was attacked and killed by the latter’s mob. It had nothing to do with her sex and everything to do with her connections..

Also exaggerating what our ancestresses were up against does nobody any good..

Yes. Only problem is that the author doesn’t know her fashion history. A corset does not drastically alter your voice, if it does at all, because a properly fitted one doesn’t do reduction in the upper torso. You speak and breathe normally, which she would know if she had ever tried one on. But popular lore says otherwise and so we get these misconceptions. Also, by the time radio was a thing c.1920s, women weren’t wearing corsets anymore. Some were wearing brassieres, but they were lightweight and they weren’t the right shape to constrict a woman’s diaphragm. So the shrill voice, I’m guessing, was a product of the radio itself and of society’s prejudices against women.

25 and 26

Thanks for the additional detail. And yet after this conflict, both the men, Orestes and the future Saint Cyril, were alive and talking, and Hypatia was not.

Looking for a more recent example? How about the refusal of temperance organizations to let Susan B. Anthony speak? How about the refusal of the World Antislavery Congress in 1840 to seat the female members of the US delegation, including Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, which ultimately led to the first US women’s convention at Seneca Falls? Amazing, how the sexism of reform groups helped launch the women’s movement in the US. Inspiring to remember how these women refused to be silenced and insisted on raising their voices in public.

Cyril and Orestes had better security obviously.

Lily @27

A well supported voice comes from the diaphragm which isn’t part of the upper torso, and is exactly where corsets usually restrict the body.

In light of the church’s teachings against women, it’s good to remember that the first people to witness the risen Jesus were women- people whose voices were less likely to be believed as heralds of his return, but also those who never deserted him, even in death. Much like the announcement of his birth to shepherds in the field rather than to kings, Jesus speaks in ways that society rarely mimics, and in my opinion in the ways they should.

The apostle Paul on the other hand..

@27: I’ve heard Sandy Toksvig and some very deep-voiced women described as “Screeching” and “Shrill” by misogynists, so you have my complete agreement that it is attitudes, not reality, shaping this problem.

@30: A properly fitted and adjusted corset should have very little effect on the diaphragm, however, most corsets are badly fitted, rarely made for the individual and common knowledge is that it should always be tight, which is wrong on all three counts: the result of bad corsetry and anti-feminist influence. Also, the diaphragm is also known as the inferior thoracic border… as close to meaning ‘bottom of the upper torso’ as you can get.

berthulf @34 but when the diaphragm contracts it flattens from dome shape, pushing the intestines further down into the lower torso, which responds by expanding the stomach slightly to make room for them. If the lower torso is consticted at all or even just stopped from expanding that small amount it will affect the amount of air you can inhale. Try it, put your hands on your stomach and breath in deeply, you will feel your stomach gently pushing out as you breath in. I don’t see how a corset that was tight enough to actually offer any support could not restrict that movement. You can breath simply from the upper torso and a surprising number of people do, but that will not support the voice as well, which is why breathing lessons are part of singing and voice lessons.

Thanks for this piece. *fistbump*